As part of Big Circulation—my ongoing global journey as a human bridge connecting people, cities, and ideas—I arrived once again in London, stepping into Marylebone under a grey sky and quiet rhythm.

The concept of circulation has always fascinated me: not just how goods or people move, but how ideas, systems, and values migrate, adapt, and root themselves in unfamiliar places.

That morning, I paused in front of a storefront I had passed many times before: Cancer Research UK.

Three familiar words. But this time, as I stepped inside, I was struck by three others: Cancer, Commerce, and Charity.

From Shops to Science: How Retail Fuels Research

Cancer Research UK operates over 600 charity shops across the United Kingdom, making it one of the largest non-profit retail chains in Europe. But this is no ordinary retail business. These stores don’t exist to push margins or expand market share. They exist to fund something far more urgent—the future of cancer research.

Yet for many international visitors, especially those unfamiliar with the UK’s charity shop culture, the scene can feel dissonant.

“Why is a cancer research organization selling clothes?”

That question is more common than you’d think. The sign implies laboratories, sterile environments, perhaps clinical trials or medical journals. But beneath it: racks of used jeans, vintage handbags, worn novels, and porcelain tea sets.

It may seem like a mismatch. But it’s not. In fact, it’s one of the most brilliant integrations of public health funding, civic engagement, and sustainable commerce in modern Europe.

Each donated item becomes a small act of solidarity.

Each purchase becomes a micro-investment in science.

In this structure, the everyday becomes meaningful—and public health research is no longer the domain of specialists alone.

Jamie is a volunteer at the Cancer Research UK Marylebone store, driven by a personal connection—his grandfather was a cancer patient.

Meet the Volunteers: Maria & Jamie

Jamie & Emma in the shop

Redefining Public Participation in Health

There is something fundamentally democratic about this model. The shop doesn’t ask you to be a doctor or a donor. You can participate simply by giving away a jacket you no longer wear. Or by spending £3 on a paperback. Or by volunteering a few hours a week.

These micro-engagements scale. They fund clinical trials. They support epidemiological research. They help Cancer Research UK keep some of the best scientists in the world on the front lines of discovery.

The shop, then, is not just a space for exchange.

It is a platform for contribution. A public square for science.

Ethical Living as Preventive Care

What elevates this model even further is its philosophical alignment between what it promotes and what it funds. Cancer Research UK supports research into how lifestyle, environmental factors, and consumption patterns influence cancer risk. It campaigns for awareness around smoking, obesity, pollution, and early detection.

And what better way to practice that ethos than through circular fashion, reuse, and community-driven commerce?

Every secondhand purchase resists overconsumption.

Every item reused delays landfill accumulation.

Every donation bypasses waste and reactivates value.

In a world increasingly aware of its ecological limits, these shops do more than raise money—they model the kind of conscious, sustainable living that strengthens public health at its root.

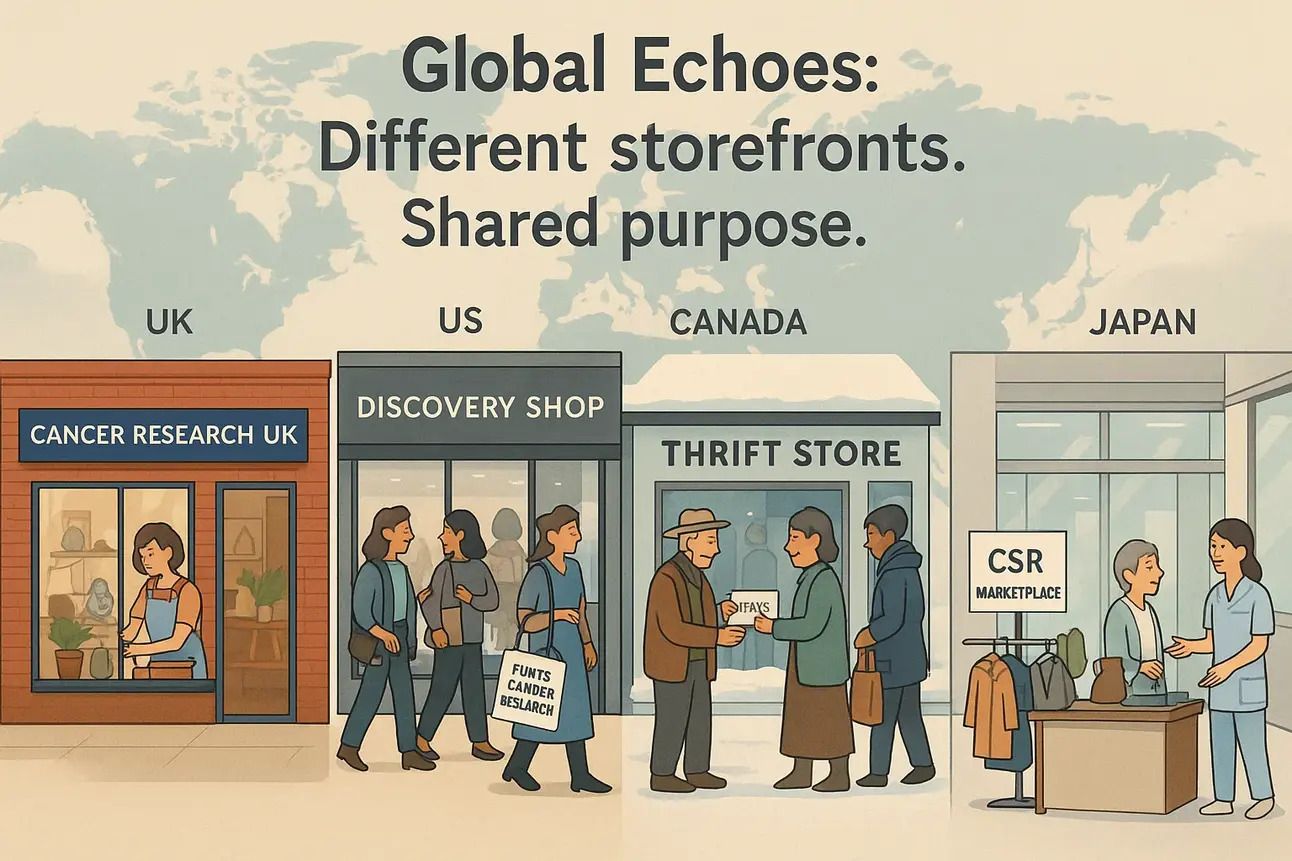

Global Echoes: Variations on the Model

While the UK may be a pioneer in charity retail linked to medical research, similar models are emerging globally—each adapted to its cultural context.

In the United States, the American Cancer Society operates Discovery Shops, retail spaces offering curated secondhand goods to fund cancer research and patient services.

In Canada, the Canadian Cancer Society runs thrift stores whose proceeds support transportation and lodging for rural patients traveling for treatment—bridging access gaps while involving local communities.

In Japan, the model takes a different shape. Though traditional charity shops are rare, hospitals and corporations are experimenting with pop-up retail, donation-based marketplaces, and CSR-driven resale platforms as part of broader wellness and aging society strategies.

The common thread? The shop is not just a point of sale. It’s a point of contact—with community, with ethics, with care.

Toward a Civic Economy of Health

What Cancer Research UK is building is not a retail empire. It’s a civic infrastructure—an ecosystem where care becomes capital, and shopping becomes a subtle but powerful act of public investment.

By activating familiar behaviors—donating, buying, browsing—it decentralizes participation in scientific progress. And by embedding that participation into daily life, it reclaims health as a collective endeavor, not a specialist field.

This is what public health infrastructure can look like in the 21st century: not cold institutions, but warm, accessible spaces in our neighborhoods. Spaces that are ordinary on the surface, but extraordinary in function.

When Small Acts Build Big Systems

And so, as I stepped away from that modest Marylebone storefront—where Cancer Research UK sells more than clothes—I wasn’t just leaving a shop.

I was leaving a glimpse into a future.

A future where Cancer prompts systems change, not just sympathy.

Where Charity evolves into collaboration, not just contribution.

And where Commerce quietly powers impact without losing its soul.

In this subtle choreography of C-words—care, community, circulation—we may find the seeds of something transformative.

Not in the headlines. Not in the institutions.

But in the everyday spaces where people show up, give quietly, and build new meanings from old coats.